Year one of computer engineering at PICT didn’t quite sparkle as I’d hoped. I dreamed of diving headfirst into new programming languages, crafting software applications daily. Sure, the classes on computer hardware and microprocessors were intriguing, but the rest? Entirely superfluous in my book.

Thermodynamics? Engineering Drawing on actual paper? Mechanical workshop projects? What the hell was this? I might as well have chosen civil or mechanical engineering if I’d wanted that.

Where was the cool stuff? Operating Systems, Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality? Having grown up on a steady diet of Star Trek and sci-fi movies, that was the reality I was ready for.

Year two? Even worse. More classes like Strength of Materials, which haunted me for three semesters, and Linear Circuits, which I had zero interest in. I found solace in nurturing my other passions—playing guitar and organizing social events like college festivals, project exhibitions, and the college magazine. These were rewarding, filled with music, camaraderie, and a bit of fame.

I transformed from a full-blown nerd into a long-haired, earring-wearing, guitar-playing college dropout.

My parents? They were freaking out. Both being medical doctors, they had hoped that I would become one and when I chose to attend PICT instead, they were extremely apprehensive. And now they were legitimately freaking out.

लौकिक अर्थाने पोरग बिघडल ! (“Proverbially, the kid went off the rails”)

This wasn’t the future they envisioned. I knew they were in despair, but I was too engrossed in having fun. Not that I wasn’t learning—I passed all the computing subjects, flunking the non-computing ones out of sheer disinterest.

The only reason I remained enrolled in PICT was the University of Pune’s Jaykar Rule – the famous “ATKT” or “Allowed To Keep Term” rule. It allowed students to keep their term if they failed fewer than four subjects. So, if you failed two subjects in the first year, you could move on to the second year, provided you passed those subjects before starting the third year. This rule underscored how common this scenario was for many students.

From 1987-1990, those formative years shaped my entrepreneurial instincts, instilling a boldness I’d carry into the future. I was part of every social club, sports club, and music gathering at PICT and beyond. Pune, a college town, had a vibrant student scene with famous and infamous colleges connecting through festivals.

One standout was the InSync festival at Fergusson College—a multicultural bonanza of arts, music, culture, writing, poetry, and, naturally, the sport of hooking up with girls. My PICT crew and I made our mark, winning awards and gaining confidence.

This set the stage for the granddaddy of them all: Mood Indigo at IIT Bombay. For those in the know, Mood Indigo is a five-day carnival of high-energy events and zero sleep. It spans the entire IIT campus, with students housed in hostel rooms and living the full IIT experience. My first attendance in 1989 was exhilarating to say the least.

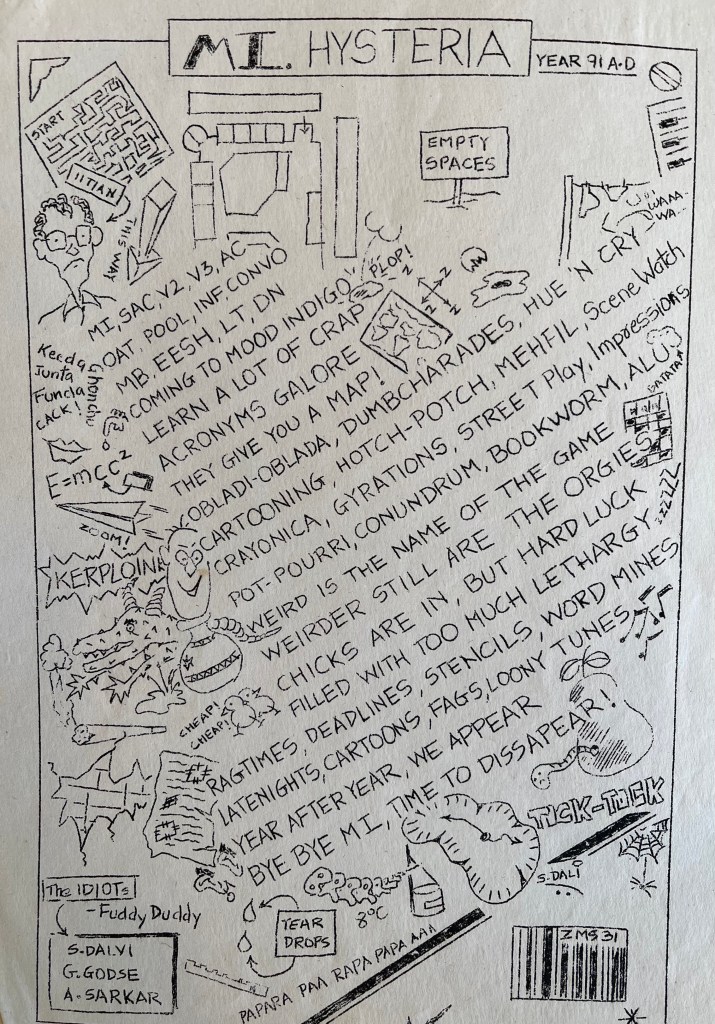

By 1991, I was back with my PICT classmates, reveling in the festival. We won the Rag-Mag competition, aced quiz contests, and excelled in art. Not bad for a bunch of computer nerds.

Then came the pivotal butterfly moment.

Post-event, while others sought out the usual vices—sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll—I was more the hex, plugs and rock ‘n roll type of nerd. Drawn to the state-of-the-art, air-conditioned computer lab. The labs at IIT Mumbai, surprisingly accessible, allowed me to wander in. There, amidst drool-worthy Intel 386 and 486 PCs, I spotted a Unix shell on a screen—a tantalizing alternative to the familiar MS-DOS or Windows 3.1 interfaces.

Striking up a conversation with the student seated at that computer, I discovered it was Linux—an open-source Unix variant. Unlike the only other OS code I’d seen only on paper, Minix, Linux was freely available to use, modify, and distribute. This was groundbreaking. The student had only learnt about it because all the IIT labs were then connected to the Internet. Something that I had just learned of a couple of months ago. It was a rudimentary Internet with no websites, no browsers and only a command line interface. Another student named Linus Torvalds, far away in Finland had written Linux from scratch based on ideas from BSD, Minix and some other variants. I would eventually meet him in San Jose in 1999 at LinuxWorld. But that’s another story.

I spent the night copying Slackware 0.99 Linux onto thirty 1.44” floppies. I cajoled the student to “loan” me the floppies on the promise that I would bring them back in a few days. Which I did.

Back at PICT, I convinced our computing lab teacher, Mr. Varma, to let me install Linux on a PC with a hard-drive. Booting it up, my nerdy classmates and I marveled at our newfound power. We no longer needed pirated copies of Windows or MS-DOS. We had an entire operating system, for free, with endless apps at our fingertips.

This was PICT’s first Linux installation ever, and none of us were prepared for the tidal wave it would unleash on the world—and on me.

The butterfly had taken flight.

Linux became the cornerstone of my second startup—India’s first ISP, WMINet, launched in 1997. It also underpinned my third startup, moreLinux, in 1999.

Today, Linux is omnipresent—in every computing device, car, phone, appliance, and perhaps even your electric toothbrush.

But back in 1991, it blew my mind, and I was never the same again.